Why did it take so long for COVID to be recognised as an airborne disease?

CREDIT: This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared on The BMJ

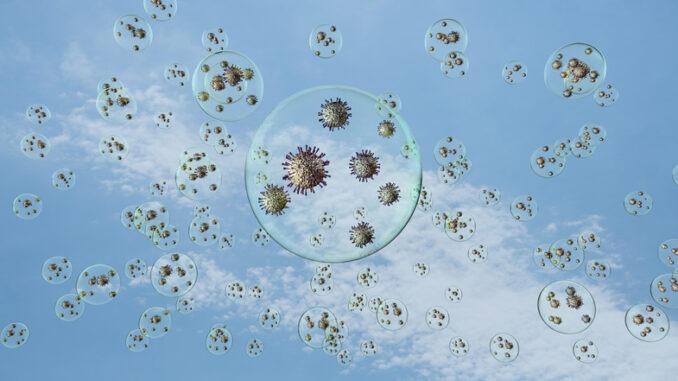

The world is finally coming to terms with the realisation that transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is airborne. First came the modelling studies, sizing up airborne particles, their trajectories, and viral load; then came examples from the real world, filling the gaps in the models and confirming that the pandemic virus is chiefly spread through tiny, aerosolised, respiratory particles.

Trying to validate this by detecting live virus, however, is fraught with technical difficulties – hence, the frenetic attempts at measuring the quantity of infectious virus in breath, as well as revisiting knowledge on ventilation sciences. Although keeping your distance, wearing a mask and getting vaccinated have provided much protection, one intervention that would have a significant impact is adequate indoor ventilation.

Healthcare, homes, schools, and workplaces should have been encouraged to improve ventilation at the very beginning of the pandemic, but tardy recognition of the airborne route by leading authorities in 2020 stalled any progress that could have been made at that stage. This was compounded by controversies over the terms ‘droplet’ and ‘aerosol’ as the definition of these dictates different infection prevention strategies, including type of mask.

Inserting the term ‘ventilation’ into a COVID-19 policy document might appease readers, but ensuring people get enough fresh air in indoor environments seems to have fallen by the wayside. Why is this? Can we establish the reasons for this, seemingly lethargic, response to improving indoor air quality?

In order to answer, it is imperative to understand three fundamental principles of infection prevention and control. Firstly, most pathogens are invisible, secondly, you know the system has failed only when there is an outbreak and, finally, you cannot always identify a specific cause, making it difficult to implement the most appropriate intervention. Infection control relies on a bundle of measures that are assumed to cover most transmission routes, explaining initial misguided emphasis on droplets and surface risk, rather than unconstrained aerosol.

Nebulous air

Common sense dictates so much of what is done for infection control, since most funding bodies consistently prioritise the most immediate, urgent, or commercially beneficial societal problems. Furthermore, current guidelines tend to focus on solid bodies, such as people, surfaces – both hard and soft, equipment and water. Air is, literally, nebulous. Just as cleaning was the Cinderella of infection control during the past decade or so (methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus sorted that out), we must now confront the neglected, but substantive, role of air in transmitting infection. It is fair to say that air could be the final medium to define and standardise within the infection control itinerary.

Another major compelling reason that air quality has been side lined is cost. Most buildings are neither designed nor well operated from the air quality aspect, with energy conservation and thermal comfort at the top of the list of requirements. Pumping in adequate amounts of fresh outside air, however engineered, will challenge running costs as well as carbon status.

Outdoor air generally differs from indoor air in terms of temperature and humidity, and conditioning outdoor air needs significant energy. While evolving green technologies might be able to offset some of these increased energy requirements, any revision or upgrade of existing systems is a big undertaking – and enormously expensive. Additionally, ventilation is usually controlled by building operators and owners, not necessarily individuals, and the former are not yet mandated by law to improve ventilation in public venues.

Ventilation and air cleaning systems are noisy, drafty and require fine tuning and regular maintenance. Even simple window opening invites discussion over chill, airflow, and security. There are some standards for indoor air quality, notably through proffered air changes, but these, chiefly, concern specialist healthcare environments such as operating theatres. Indeed, existing ventilation standards hardly consider the risk of airborne infection in non-specialist public spaces at all.

Miasmic uncertainty

So where are we now with indoor air quality? Clearly, better ventilation requires planning and investment, but who is going to ensure this, and how should it be done? Upgrading internal air quality for billions of indoor environments in the world needs solid research, funding, and mandated standards; those that we currently have are variable or are applied inconsistently. We have established public health strategies for foods and water and even pollution, but air quality inside most public venues in our communities resembles nothing more than miasmic uncertainty.

As with all major shifts in scientific understanding, tackling the final medium requires courage, investment and political support for both scientists and policy makers. The same applies to business and industry, which are already producing a range of air cleaning technologies and equipment.

We cannot ignore airborne transmission any longer, however difficult or costly it may be to control. It is time to accept the fact that most people acquire SARS-CoV-2 by breathing in contaminated air. Window opening is a start, but it is not a panacea for COVID-19 or, for that matter, any other airborne viruses in the 21st century.

Be the first to comment