COVID-19 is a stark recent example of how health inequalities persist for people of ethnic minorities. How can communities, professionals and services tackle the systemic injustices that affect everything from diabetes to mental health? Samir Jeraj reports

CREDIT: This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared on The BMJ

When Sanisha Wynter sought help for her mental health, she struggled to access services, treatment, and support—and above all to be heard by the professionals she saw and the services she attended. Her story is disturbing, yet familiar. One clinician told her she was a “strong Black woman,” drawing on a racialised stereotype that downplays the emotional and physical pain that Black women experience.

Later, Sanisha was referred to a therapist who told her that she had never treated a Black or bisexual woman before, placing the onus on Sanisha to educate her about race and sexuality. “My trauma took a back seat to facilitating her understanding,” she said.

Sanisha’s story opened an event on 9 March organised by National Voices, a coalition of 160 health and social care charities, which aim to examine ways to tackle racial inequalities in health. Unless experiences like Sanisha’s are publicised and considered, she told the conference, “racial injustice and health inequity can be dismissed.” The risk is that biases “overshadow the conversation,” ultimately leading to poorer health outcomes.

Undermined trust in services

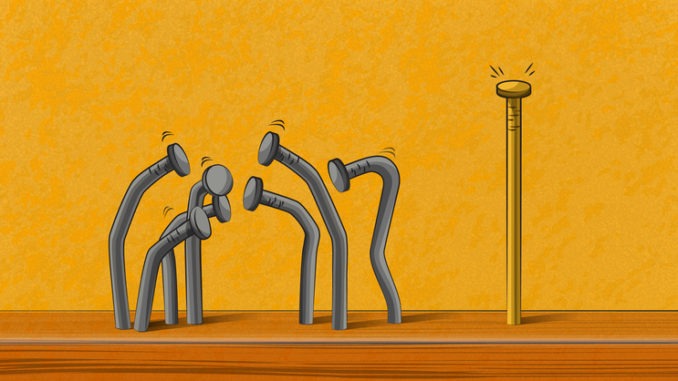

Individual professionals’ biases and actions can create poor experiences for patients and give rise to the narratives that undermine trust in health services – but this is just one part of a much larger picture of structural inequalities across health, housing, work and education.

Another speaker, Habib Naqvi from the NHS Race and Health Observatory, explained that the observatory focuses on these “causes of causes” in health inequalities, looking for the reasons that people of ethnic minorities are more at risk of developing diabetes and hypertension, for example. The observatory works with community organisations as the “eyes and ears” on the ground, hoping to create “meaningful and sustained change.”

Among the first questions the observatory considered was why Black women experience higher risks in pregnancy and maternity. In 2020 MMBRACE, a UK collaboration that looks at maternal and infant deaths, found that Black women were four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women, and Asian women were twice as likely. Like many racial health inequalities, this discrepancy had been known about for years, if not decades, but had not been the focus of the sustained work needed to change these outcomes.

Habib Naqvi said that responses to racism needed to look at the level of the individual, such as “racial bias in clinicians’ assumptions around things such as pain management,” as well as policies and practices, and the evidence on which health interventions are commissioned. For example, although the number of older people of ethnic minorities with dementia is growing, poor data collection by the NHS means that the ethnicity of about half of dementia patients is unknown.

“If we don’t talk about the outcomes, and results, we’re pushing blame and responsibility onto patients who are seeking treatment and might have different needs,” said Halima Begum, chief executive of the race equality think tank the Runnymede Trust.

She emphasised the importance of socioeconomic class to understanding why people of ethnic minorities have poorer health outcomes. In the labour market, people of ethnic minorities continue to be over-represented in the occupations that place an individual at high risk of infection with COVID-19; transportation, health and social care and the food sector.

They are also more likely to live in poor quality and overcrowded homes, to experience poverty, and to be in poorer physical health. There is a ‘socioeconomic duty’ in the 2010 Equality Act which would compel public organisations to address class inequality, but it has never been implemented.

Racist assumptions

A major, systemic, problem is that the voluntary and community sectors have a poor record of action on racial inequalities, and in representation among staff and board members. In 2019, the Charity So White campaign encouraged current and former staff, volunteers and service users to highlight problems, from racist assumptions in training, to tokenistic action in workplaces, and the ‘white saviour complex’ exhibited by some people in the sector.

This campaign, together with events such as Black Lives Matter, led to some charities confronting these challenges. Birthrights, which focuses on the human rights of pregnant women and birthing people, has made efforts to become a more inclusive organisation and to act on racial inequalities in pregnancy and maternity. The charity currently is running an inquiry into systemic racism in maternity care, drawing on patient experience, medical expertise and partnership with other organisations to advance understanding of the issues behind the data and to develop solutions.

“We were an all-white team and an all-white board of trustees, like many in the charity sector,” said Amy Gibbs, chief executive of Birthrights. It recruited new board members, changed how it runs staff recruitment – for example, sharing interview questions in advance, which is recognised to help ‘level the playing field’ for candidates from under-represented backgrounds by focusing on performance rather than experience – and started an internal programme of ongoing training. Amy Gibbs is clear, however, that Birthrights is still on its journey.

The phrase ‘doing the work‘ is often applied to the individual efforts that we should all be making to understand our prejudices, ignorance and biases, and how they affect the people around us. Organisations and institutions will also need to ‘do the work’ if we are to unpick centuries of compounded racial inequalities.

Many have already started meaningful change; many others will need resources and accountability in order to tackle racial inequalities in health.

Be the first to comment