What is Lyme disease? And how do you contract it? Find out below

CREDIT: This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in The London General Practice

“Lyme disease is an infection caused by a group of bacteria transmitted through an infected tick, giving you a specific set of symptoms,” says Dr Sanjay Mehta, GP at the London General Practice.

According to an analysis published in the open-access journal BMJ Global Health, more than 14% of the world’s population probably has or has had, tick-borne Lyme disease. But Mehta says you can’t catch it from any tick, only infected ones.

The disease can also be seasonal – “It doesn’t die down to zero, but it drops significantly during summer and winter, and peaks during early autumn and spring,” he says.

What are the symptoms?

Lyme disease can manifest in a variety of different ways – from being asymptomatic to nerve damage, in more severe cases.

“There are two main groups of patients,” says Mehta. “First, there’s the group who catch it early, and they don’t really get any symptoms – they just see they’ve been infected by a tick.

“Then there’s the second group of people who don’t get treatment, and although only a very small percentage of them actually end up with symptoms, they are the ones we worry about.

“Those patients tend to get three stages of symptoms. First, they might get flu-like symptoms kicking in a week or so after the bite, and a characteristic rash. Second, some might then get symptoms related to their nerves, their heart and their brain, several weeks or months later.

“An even smaller number of people might then get the third stage, and these are the symptoms people typically associate with Lyme disease – long-term joint problems and neurological symptoms.”

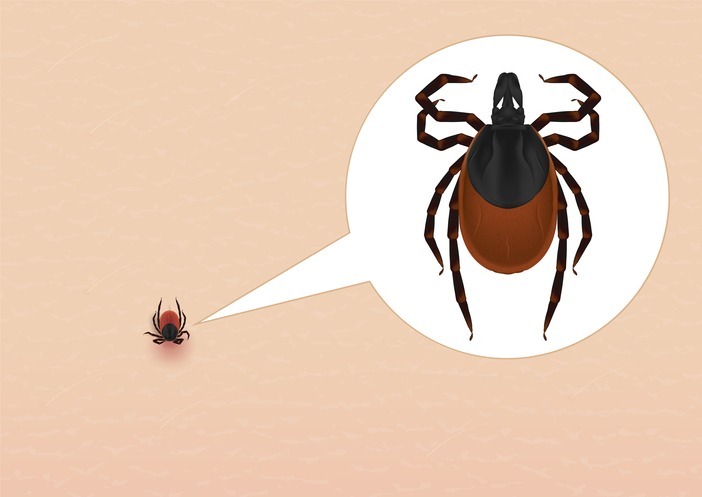

How do you contract Lyme disease?

As Lyme disease is passed on exclusively via infected ticks, you can downgrade the disease from unlikely to highly unlikely by avoiding tick-heavy areas or taking precautions within them.

“There are areas of the UK known to harbour infected ticks, like the Lake District, the New Forest, the North York Moors, and the Scottish Highlands,” says Mehta. “If you see ticks on your skin, you don’t necessarily get transmission for up to four hours, so if you can remove them, that’s ideal.”

If you are going to any of these areas, there are also a few simple things you can do to limit the risk. “Try to keep to paths in grassy, wooded areas, and keep away from long grass and vegetation,” advises Mehta. “It sounds obvious, but shower on your return – often ticks fall off – and check yourself for them too. Wear insect repellent, long T-shirts, and long trousers if possible.”

What should you do if you get bitten?

The simple answer is, if you’ve gone to a high-risk area and you know you’ve been bitten by something, see a doctor.

“It is worth going on to treatment, which is a course of specific antibiotics,” says Mehta. “We do run tests, and the tests are fairly reliable, but the main things are a) have you gone to a risky area? b) have you seen you’ve been bitten? And c) have you developed symptoms?”

“The take-home message is to seek medical help if there is a bite, but be aware, it’s only a small percentage of people who end up with problems.”

Be the first to comment