As reported by The Times, more than 720,000 people in Britain could benefit from groundbreaking new drugs that slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, experts say

Scientists will tomorrow reveal the first detailed results of a landmark trial of donanemab, a treatment for early Alzheimer’s. The US pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly announced in May that the trial had been successful, slowing cognitive decline by about a third over 18 months, but will give the full results at a medical conference in Amsterdam.

The announcement comes after a similar drug, lecanemab, made by the Japanese company Eisai, was earlier this month licensed for use in the US after trial data showed it could slow decline by a quarter.

After years of trial failures, the two treatments are the first successfully to delay the relentless progression of Alzheimer’s.

“This is a new era,” said Richard Oakley, associate director of research at the Alzheimer’s Society. “There is still a long journey ahead, because this will pave the way for better drugs, but I’m really excited.”

Scientists are keen to see how donanemab affects different groups of people, including those with genetic mutations, at different stages of the disease. Details of side-effects and the duration of the beneficial effect will also be closely examined.

If approved in the UK, the drugs could be used to help 720,000 people, according to estimates by the Alzheimer’s Society and Alzheimer’s Research UK. That includes 435,000 people with mild cognitive impairment — a precursor to full-blown Alzheimer’s — and 286,000 with mild Alzheimer’s.

Amanda Pritchard, NHS England’s chief executive, said the health service was setting up a team to oversee the roll-out of the drugs

Identifying those people is a bigger problem. Only 62% of over-65s with dementia in England currently have a formal diagnosis — and getting one takes up to two years. Too often, when patients do finally receive a diagnosis, they are just told they have broadly defined “dementia”.

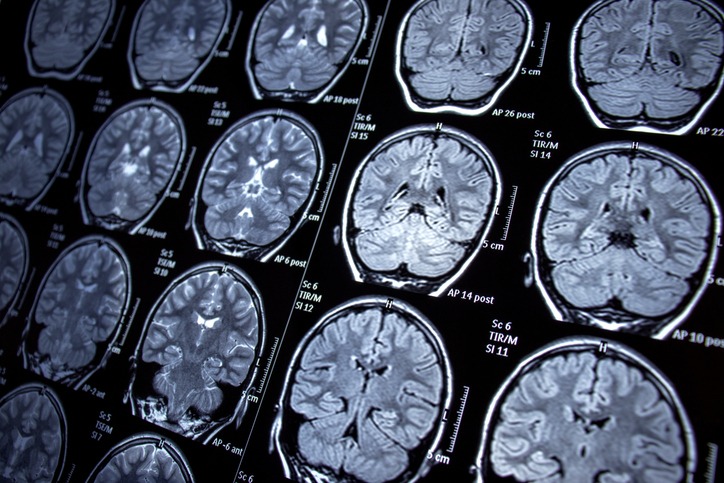

These drugs, which are given by drip in hospital every few weeks, clear away amyloids, toxic proteins that clog up the brain. As a result, they work only for people with early-stage Alzheimer’s — not other forms of the disease, such as vascular or frontotemporal dementia — or mild cognitive impairment with a positive test for elevated amyloid.

This amyloid can only be detected with a lumbar puncture or a PET scan — 3D internal imaging. But with just 88 PET scanners in the UK, experts believe a vast infrastructural change is needed if patients are to access the drugs.

Only two per cent of dementia patients receive the detailed diagnosis they require to be eligible to receive the new drugs.

NHS England has set up a team of officials to crack these problems before health regulators have finished assessing the drugs, which is expected to happen next year.

NHS England’s chief executive, Amanda Pritchard, said the new treatments “could make a real difference” to people with early-stage Alzheimer’s.

“The NHS is a world-leader when it comes to rolling out cutting-edge treatments,” she said. “In NHS England, we are setting up a dedicated team to plan for the roll-out of a new class of drugs as soon as we get a green light from the MHRA [Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency] and Nice [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence], who . . . have to assess the safety and clinical and cost-effectiveness of the treatment.

“We are already thinking about how we can ramp up scanning, treatment and monitoring capacity to deliver these drugs to eligible patients and improve the quality of their lives and their families’ lives.”

Susan Mitchell, head of policy at Alzheimer’s Research UK, said it is vital the drugs are not overpriced. “We want to make sure it gets to the people who need it, so it needs to be valued appropriately. And we need to have an NHS ready to deliver it to patients who need it.”

Oakley said: “There is a huge challenge ahead. We’ve got disease-modifying treatments coming through, but we don’t have the capacity to give them, we diagnose people too late and not specifically enough at the moment, and we don’t have the infrastructure we need.

“But this is the biggest opportunity we’ve ever had in Alzheimer’s disease, because we now have treatments which slow down the progression of the disease for the first time in its 110-year history.

“We believe we have an opportunity to remodel the health and care system to ensure we benefit from these breakthroughs.”

The results will be presented tomorrow afternoon at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Amsterdam.

Be the first to comment