A disturbing side to this pandemic – and possibly the most damaging – has been the sheer amount of misinformation that has dominated social media which, unfortunately, has affected public perceptions, argues Survindar Chahal of First Practice Management

Numerous doctors, politicians and scientists are providing detailed analysis – but, somehow, your Uncle Charlie still thinks it’s all a hoax to trick people to get a microchip vaccine – which was made from Professor Chris Whitty’s elbow patches – that will track your movements.

The World Health Organization has warned that we are fighting an ‘infodemic’ as well as the coronavirus. “We’re not just battling the virus; we’re also battling the trolls and conspiracy theorists that push misinformation and undermine the outbreak response,” said Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, director of the World Health Organisation.

Being in lockdown, then partial lockdown, then a new tier system, then announcing a fourth-tier days before Christmas advising people to stay in their homes and not to travel (whether you’re travelling for legit reasons or just testing your eyesight), has been roundly criticised for the confusion it has caused, prompting people to look elsewhere for a clearer – or alternative – message.

How social media has confused the COVID risks

The information on social media is high in volume and low in quality, which makes for a dangerous mix; users are bombarded by information every day, and viral misinformation spreads faster than the virus itself. If their favourite personality tells them that it’s all a hoax (it’s not), the masks won’t work (they do), the virus will die off in the summer (it didn’t) or a bit of bleach will cure it (it definitely won’t), they are not likely to follow the safety guidelines.

An IPSOS poll of over 2,200 British people showed that 30% think the virus was created in a lab, 14% believe the death rates are being exaggerated on purpose by the authorities and one-in-20 (7%) think that the virus doesn’t really exist. The people who believe these theories are more likely to get their news from social media – 56% of those who think COVID is a myth got their information from Facebook.

Facebook and Twitter were slow to react to this, and were criticised for it, and swiftly started posting ‘reality check’ links on virus-related posts to emphasise trusted sources like PHE and the NHS, removing false vaccine claims “that have already been debunked by public health experts”. YouTube took down over 200,000 videos with dangerous, misleading or medically unsubstantiated claims.

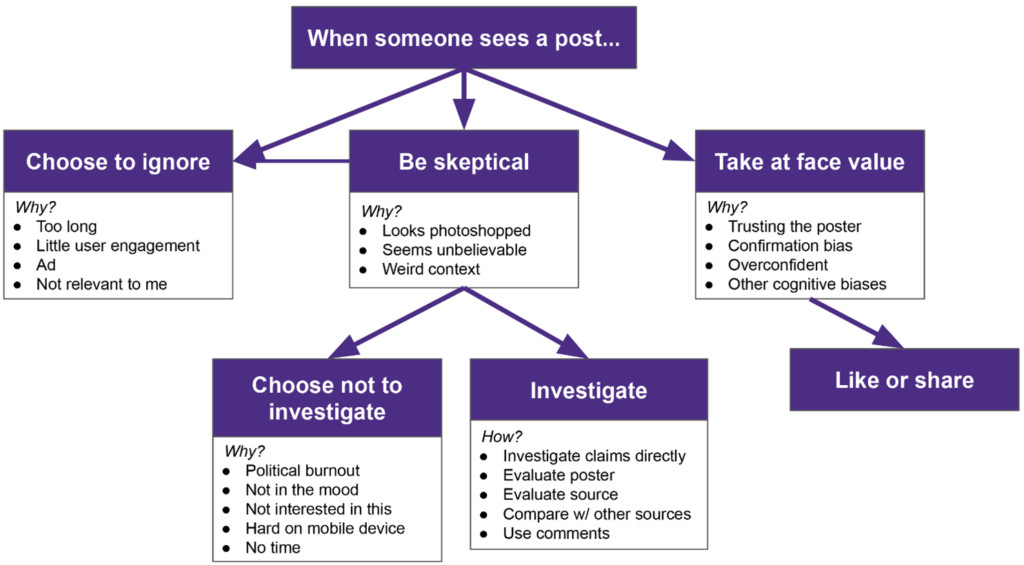

A study by the University of Washington looked at how people responded to posts in their social media feeds, finding that participants ignored posts that were deemed too long, overly political or not relevant to them. Although the study was small scale, it did provide an understanding of how to help people resist misinformation in their feeds.

Tackling patient beliefs in misinformation

People don’t always have access to qualified information to determine what news is accurate or not – TV, radio, social media and ’alternative’ sources present information that is complex, confusing, incomplete or wildly inaccurate. Conflicting information on government actions and behaviour was also a factor. “As the pandemic has gone on, there has been little attempt to clarify conflicting messages, and this must end,” said BMA chair Dr Chaand Nagpaul in September. First Practice Management produced a series of ‘COVID MythBusters’ articles because of questions around how to educate patients – and staff – on what is real and not real when it comes to COVID or the vaccine.

Correcting these ‘inaccuracies’ might feel frustrating, but it is an important skill for clinicians engaged in 21st century healthcare; it means using the latest reliable evidence that applies to the patient and communicating the ‘what’ and ‘why’ so patients can easily understand complex scientific messages.

Use bad information as a learning moment

Clinicians and practice staff are critical in helping patients understand what their diagnoses and treatment plans mean to them. Sharing factual information, and engaging with them on a personal level, are key to successfully delivering quality care – as is being careful not to make them feel bad for listening to a contrary opinion that they have mistakenly take as fact.

Active listening

To stop a patient from embracing a myth, address all their issues. Take time to listen and process how they feel about something they’ve heard, and ensure they fully understand all the information, so they are less likely to believe the falsehood.

The risks of self-diagnosis

By the time they get to your waiting room, a patient might already have decided what they could be facing; their self-diagnosis not only causes undue anxiety but also makes the consultation harder if they have convinced themselves it’s bad news. Explain that, while being informed is important, there’s no substitute for expert advice from a medical professional who has performed an examination and has access to their medical history.

Credible and reliable resources

Most online forums and support groups are helpful, and credible health resources will advise readers to check with a GP or NHS services for definitive advice. Use it as an opportunity to help patients in their research – for example, provide free educational materials on-site and, if available, refer them to online resources from the NHS.

If you use TV screens in the waiting room, use them to show information on where to find the latest information, or some of the advisory content from PHE, NHS or the GOV.UK websites. Most importantly, keep an open dialogue with patients. If they are doing their own research, or asking whether something is true, they’re keen to take the right steps to keep them and their loved ones safe.

By helping patients access the right information, we will improve outcomes, engagement and increase patient satisfaction overall.

Be the first to comment